In her exceptional study on fairy tales, From the Beast to the Blonde, Marina Warner, in a single sentence, sums up the true worth of fairy tales: “for they are stories with staying power, as their antiquity shows, because the meanings they generate are themselves magical shape-shifters, dancing to the needs of their audience.”

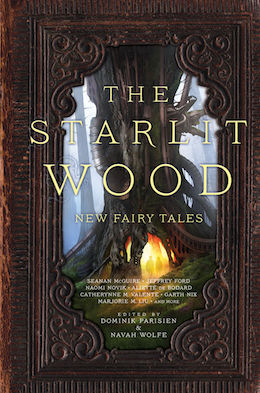

With this succinct and elegant explanation as to why fairy tales entice our continued fascination, I’ve found my entry into The Starlit Wood—an ambitious anthology collecting eighteen fairy tale retellings drawn from various traditions.

Fairy tales possess an almost deceptive simplicity in the way they’re told. They’re light on a storyteller’s tongue, quick to burrow deep into memory, and infinitely malleable. It’s a chief reason we see fairy tale characters reimagined into completely different literary traditions and properties, and it’s not incidental the anthology opens with “In the Desert Like a Bone”—an Old West-style retelling of “Little Red Riding Hood” that’s as dry and hardened as the very desert itself. Seanan McGuire remains faithful to the tone of the original, instantly recognized and beloved, even as she conjures an air of severity and harshness synonymous with the Wild West. McGuire has written a predatory narrative and it circles received and unexamined assumptions—the so-called Known-by-All Truth—with bared teeth. Ultimately, “Little Red Riding Hood” is a story about innocence lost as much as it is about betrayal and, consequently, growing up. McGuire understands the story’s fundamental nature, and reframes it to great success.

While they first found success in France as a literary genre in the 17th century, fairy tales are rooted in oral traditions; delivery matters. Does a story sound as a fairy tale should when read out loud? I often ask this question when reading direct retellings, revisionist takes, and complete reimaginings of fairy tales, as the mode of operation is crucial to the success of the endeavor. Editors Dominik Parisien and Navah Wolfe have brought truly skilled authors together in this anthology, ones who are attuned to the inner workings of fairy tales and ultimately deliver. In “When I Lay Frozen,” Margo Lanagan deploys without mercy the blissed ignorance of the story’s narrator in order to emphasize the scheming nature of her host and her lewd display of indecorum. It’s a story that flourishes by relying on the implicit to draw out the sinister undertones lurking within Hans Christian Anderson’s “Thumbelina”; a retelling sure to set your spine ashiver.

Karin Tidbeck examines the inherent discomfort of the reluctant bride trope in her sparse retelling of the Swedish “Prince Hatt Underground” in “Underground,” which first keeps intact the unquestioned social mechanisms behind bridal transactions in fairy tales, and then swiftly proceeds to rebel against them. There’s a glorious conversation between the heroine, Hedvig, and her incidental sister-in-law, Vega, that lambasts most of what women in fairy tales traditionally have to endure for a man; this is the inciting moment that initiates the subsequent subversion.

Amal El-Mohtar’s “Seasons of Glass and Iron” makes an excellent companion piece as it captures the meeting between two heroines amidst their magical tasks—an event which undermines the logic of their self-imposed martyrdom. Characterization in fairy tales often remains flat and characters tend to be puppets propelled along their journeys because the plot has gained momentum; character development is rarely more than an afterthought. The tale whisks away the heroine far from home on a punishing quest without her having much say in the matter. She’s there. Tasks need doing in the all-mighty name of love, usually, and she might as well roll up her sleeves to do the job. Through a chance storyline intersection, created as El-Mohtar bridges the narratives of “The Glass Mountain” and “The Black Bull of Norroway,” she disrupts this momentum and invites introspection instead.

The crowning achievement of the more faithful approach to retelling tales is Naomi Novik’s take on “Rumpelstiltskin,” “Spinning Silver.” Novik skillfully dismantles “Rumpelstiltskin” to its core components, gleans their essence, and then reassembles them in a narrative that dramatically alters the power dynamics of the original. Miryem embodies all the characteristics that fairy tale heroines are traditionally associated with: passivity, naivety, and goodness as a defining quality. She’s also an unshakeable force in her family and village, has a keen business sense, and can hold her ground even when facing fairy lords. All this is set up and then expanded organically, engrossing the reader with each new addition to Miryem’s story. “Spinning Silver” achieves perfection in the way it first establishes character motivation and voice, and grows from there.

The overall quality of the anthology remains high throughout, with occasional slight dips and two stories that strike me as the weakest links. Theodora Goss’s “The Other Thea” brims with many imaginative flourishes, and with Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Shadow” as source has a lot going for it, but the story lacked tension and a bit of danger needed to earn its ending. Kat Howard’s “Reflected” actively removes the journey elements from “The Snow Queen” by confining all events within a laboratory, which suffocates the story.

As I mentioned in the introductory paragraph, fairy tales are in eternal metamorphosis in accordance with audience needs, and in their continuous reexamination and reframing can emerge as unrecognizable beasts. Such is the case in “The Tale of Mahliya and Mauhub and the White-Footed Gazelle” by Sofia Samatar—a story that steals the spotlight from the feats and heroes of the story and places it on the storyteller. Samatar distresses her material, foregoes conventionality for flair, pulls the rug out from underneath the reader, and delivers the most poignant observation about storytelling and audience expectations: “[…] rather than the real person in an unexpected shape, you prefer the magic mirror, which gives you the image you wish to see, although it leaves you grasping nothing but air.”

Samatar’s observation certainly relates to my own expectations when it comes to reading fairy tale material, which I had to reevaluate while reading Max Gladstone’s “Giants in the Sky” and Daryl Gregory’s “Even the Crumbs Were Delicious”—retellings of “Jack and the Beanstalk” and “Hansel and Gretel,” respectively, both rooted in science fiction, which make their source material explicit, but quickly veer off into different territories unrestricted by the decorum of what’s expected. Is a fairy tale still a fairy tale when you strip it of all its usual identifiers, but retain the contents?

I asked myself this as I passed through the graceful and glittering space opera worlds of Aliette de Bodard’s “Pearl,” crunched grit under my boot in the canyon landscape of Garth Nix’s “Penny For a Match, Mister?”, stared captivated at the haunting performance in Jeffrey Ford’s “The Thousand Eyes” and counted missing children in Stephen Graham Jones’ “Some Wait.” For those readers who crave the thrill of the original form, these departures in delivery, voice, and tone won’t detract too much from your enjoyment, though some choices may raise an eyebrow among those expecting to stay within the familiar bounds of the Starlit Wood promised in the anthology’s title.

I still don’t know the answer to the question raised above by stories like Gladwell’s and Gregory’s, but it’s obvious that Dominik Parisien and Navah Wolfe have considered the ways in which shared cultural properties are wont to change, often beyond immediate recognition or long held expectations.

As the editors state in their introduction, “the woods were the place of monsters, of weird happenings, of adventure. That is no longer the case. […] Now the unknown is to be found in other places.” In this sense, The Starlit Wood furthers the conversation that surrounds the evolution of fairy tales in the context of a society that’s removed itself significantly from the world these tales originated from. What are our needs, now, as an audience? You’ll have to wander through the woods (and beyond) to find an answer, but it will be a wondrous journey.

The Starlit Wood is available from Saga Press.

Haralambi Markov is a Bulgarian critic, editor, and writer of things weird and fantastic. A Clarion 2014 graduate, he enjoys fairy tales, obscure folkloric monsters, and inventing death rituals (for his stories, not his neighbors…usually). He blogs at The Alternative Typewriter and tweets @HaralambiMarkov. His stories have appeared in The Weird Fiction Review, Electric Velocipede, Tor.com, Stories for Chip, The Apex Book of World SF and are slated to appear in Genius Loci, Uncanny and Upside Down: Inverted Tropes in Storytelling. He’s currently working on a novel.